The Power of Naming

This month, I’ve been thinking a lot about naming—the power it wields, and how hard it can be to call something what it truly is.

This is It Takes A Village, a monthly conversation about reading, writing, and community-building.

Welcome, lovely subscribers, lurkers, readers, and writers! So happy to have you here! A special welcome to new subscribers—we’re so glad you’ve joined our village.

High summer …and high meadow grasses and milkweed obscuring the barn

In this issue:

On the Farm

Writer’s Life

Book of the Month

Bonus: Writing Prompt

On The Farm

It’s high summer on our farm. That means drought—dry creek beds, cracked ground, and trying to keep things alive. It means sometimes running out of water, and the delicious, full-body appreciation of water when it flows from the tap. We wipe sweat from our brows and think about climate change—though I prefer the names global warming or climate crisis, which better capture the experience.

On our farm, I’m witnessing, in personal and often somewhat mysterious ways, the power and meaning of naming. Take our duck, Marigold, for example, who now lives down by the lake, but who we continue to feed and care for daily, along with nine other domesticated ducks. Marigold is the only one of our six Pekins who has a name. The other Pekin girls, all huge, solid white fluffs, are not easily distinguishable from one another. Marigold, though, has the advantage of distinctive markings on her bill. We have trouble telling the others apart, especially when they’re quiet. (The one we tried to name Beyonce can be identified only by her high, operatic quack.)

This month, when Marigold developed a limp, my husband made an appointment for her at Cornell University Animal Hospital. We’ve been there with pets before, and it tends to be quite expensive. I was hesitant to take her because of the cost, because catching her when she’s near expansive water is difficult, and because I’m pretty sure I know what’s wrong with her. My husband’s response was: “But it’s Marigold!”

Marigold with her friend, Pepper

In that moment, I realized the importance of having named this animal. Her name made her unique, apart from any other duck, and more importantly, it made her ours. Speaking “Marigold” articulated our relationship with this creature, dare I say our heart connection.

I experience a similar reaction when I walk the perimeter of the ten-acre property we’re due to acquire at the end of this month. I’m trying to learn what plants grow there, whether they’re beneficial or invasive, and what species they support. But to figure that out, I first have to know their names. An app on my phone, PlantNet, allows me to take a picture of the plant, then identify it by name. My familiarity with showy goldenrod (solidago speciosa), New York ironweed (Vernonia noveborecensis), and swamp milkweed (Asclepias incarnata) versus common milkweed (Asclepias syriaca) is growing (pun intended). There’s something about calling a plant by its name that gives me new eyes. Suddenly, I’m seeing it: the sawtooth edge of its leaves or the silvery hairs on its stem. Pronouncing the name is magical. I find myself saying, “Hello, Asclepias!” the way one would when making the acquaintance of a person, the way one would to begin a relationship. Knowing genus and species names imparts information about the plant’s relationship to other plants, too. I can look it up, find its history, uses, and dangers. Naming something changes the way I see it.

Another of my new friends: sawtooth blackberry

Writer’s Life

As writers, we’re told to be specific. Naming imparts specificity. The reader sees the thing in the mind’s eye: the deep pink of swamp milkweed as opposed to the soft lilac of common milkweed. Maybe we hear it, as in the deep baritone of the American bullfrog who lives at our pond, and who is definitely not just “a frog.”

At the same time, the orange nightmare in the Oval Office is also naming things: the Gulf of America, the Washington Redskins, the Cleveland Indians. The press, too, is busy selecting names: defense versus genocide, tariff versus tax, financier versus pedophile.

I’ve had seven legal names. This is partly due to being adopted, having confused parents, and following old-fashioned mores like taking my husband’s last name. It’s also because, ultimately, I named myself. I chose the name Barnet—long story—and made it legal. The point of my telling you this is that I’m familiar with naming, and especially the power of naming, how a name carries meaning and weight and importance. It matters what we call things, what we call people, and events, and actions. It matters because then we see.

Until last year, I never wrote the word “abuse” in relation to anyone I knew. Then an editor asked me, “Why aren’t you calling this behavior ‘abuse?’” I swear to you that it was not until that moment that I saw the behavior as abuse, but once the editor named it that, I couldn’t unsee it. It changed everything—the way I saw the behavior, sure, but also the way I saw myself and my inability to name it.

Now, I notice this inability of mine to name other things. My own confusion, for example. I have to read other writers confess their confusion, call it confusion, and only then do I recognize my own. Isn’t that why we write, though, so that someone muddling through their own confusion, their own inability to name, might read what we’ve written and be changed. Might read what we’ve written and see.

I’m writing this to you because I need to hear it myself. I need to pay the kind of attention and have the kind of courage that enables me to name without fear. Well, maybe with fear that I set aside. I have a friend who’s afraid to write about what she thinks of Israel’s treatment of Palestinians because she’s worried her Jewish friends won’t understand. She won’t name “genocide.” But if she won’t name it, can she feel it? Can she take it into herself and do something with it? I know for certain, she can’t help others to see it. It’s hard to have the attention and courage to name, and naming can have consequences, lasting consequences. But the wish I have for myself is also the wish I have for all of us: let’s be name-callers in the best sense. I believe it can change hearts.

Book of the Month

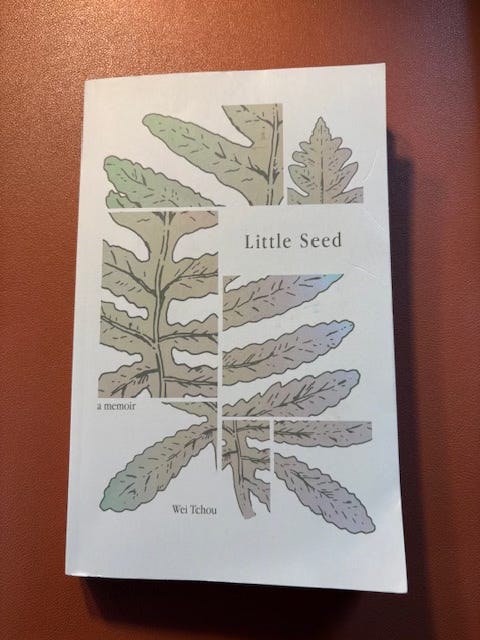

This month, I’m recommending the memoir, Little Seed, by Wei Tchou, which was a finalist for the National Book Critics Circle Award and a New Yorker Best Book of 2024. It’s the story of a young woman of Chinese descent who loves ferns and struggles with her identity.

The chapters alternate between those about ferns and those about “Little Seed,” her family’s name for the protagonist. Until three-quarters of the way through the book, the Little Seed chapters are told in third person, while the fern chapters are in first person—that is, on the rare occasion the author refers to herself in the fern chapters.

At first, I found it difficult to understand the purpose of the discussions surrounding ferns, other than their informative content and the beauty of the descriptions. But, further in, I discovered that the ferns, and the author’s close observation of them, unlock for her, and for us, truths about identity, wholeness, time, and the stories we make up about ourselves and others. I also wondered about the author’s choice of third person for memoir chapters. But when the author sets aside the third person and begins to write in first person, it’s clear that she’s inhabiting herself in a new way. We watch her unfurl, like one of her ferns, as her retrospective voice grows stronger and stronger:

…I didn’t have a freestanding relationship to the world yet; I didn’t even have a self, really, or at least not one that I could find. But relationships, like rivers, just keep moving, inexorably and at their own pace. I felt ruined and out of control in the forests around Austerlitz. But without knowing it, I was learning how to see the ferns and, by extension, myself.

The language in this book is as lush as the cloud forest in which the author finds the ferns she searches for, and in which, finally, she finds herself. The form is delightfully innovative and appropriate, revealing meaning and voice slowly over time. I could have spent much more time within these pages.

Bonus: Writing Prompt

This month’s challenge is to write about something you’re not naming or not seeing.

Is there a piece of writing that’s not working, that you’ve put away in a drawer because you’re dancing around the subject instead of meeting it head-on? Take out some pieces that aren’t working, read them over and see if maybe that’s the problem.

Is there something or someone in your life you’re not fully seeing? Make a list of possible things, situations, and people you may not be seeing, don’t feel like you understand, or could be creating stories about that aren’t the whole truth.

With these possibilities in front of you, sit quietly and challenge yourself to name what you’re avoiding in your writing or in your life. Try to give it one word you haven’t used before. Then write about that word. Use images that evoke or surround it, scenes that embody it. Get as specific as possible. Does anything shake loose?

Thanks for spending time here with me. I truly appreciate it. Feel free to recommend It Takes A Village to other readers and writers and to send along your suggestions, questions, and thoughts.

--Jillian

I love how you connected the practice of "naming" in our everyday lives to "naming" in our writing practice. I had a poetry professor tell me to create imagery with as many specific details as possible, and I've resonated with that ever since!

This was wonderful Jillian. This: ‘Naming something changes the way I see it.’ Yes, that feels absolutely right. I loved how you wove it from Marigold to your naming of weeds to the own life experiences you had been reluctant to name. The prompts are so rich. I am going to think about them & see what emerges. Certainly there are pieces of writing I have started but can’t move forward with, eluding me now, so what is it I am not naming? Hmmm….